Schoenberg’s "Erwartung" and the Structure of Desire

I originally wrote this for a blog co-authored by my master's degree cohort. It's an ongoing part of a course on Music since 1900 run by Daniel Elphick, and you can find it here.

Adorno, Theodor W., and Robert. Hullot-Kentor. Philosophy of New Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Crawford, John C., and Crawford, Dorothy L. Expressionism in Twentieth-century Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Franklin, Peter. The Idea of Music : Schoenberg and Others. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1985.

McLary, Laura A. "The Dead Lover's Body and the Woman's Rage: Marie Pappenheim's Erwartung." Colloquia Germanica: Internationale Zeitschrift Für Germanistik 34, no. 3-4 (2001): 257-69.

Ross, Alex. 2017. "The Final, Shocking Self-Portrait Of Richard Gerstl". The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-final-shocking-self-portrait-of-richard-gerstl

Schoenberg, Arnold, Leonard Stein, Leo Black, and Joseph Auner. Style and Idea : Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg. 60th Anniversary ed. London: University of California Press, 2010.

In the summer of 1908, Mathilde Schoenberg left her husband. For the first time, the 34-year-old composer was forced to confront the fact that he had virtually no understanding of what it meant to be a woman: “the soul of my wife was so foreign to me that I could not arrive either at a truthful or a dishonest relation with her”, he wrote; “we never knew each other” (Crawford and Crawford 1993: 78). Mathilde’s affair with the young artist Richard Gerstl was short-lived, and ended in his violent suicide following her return to Schoenberg in October 1908.

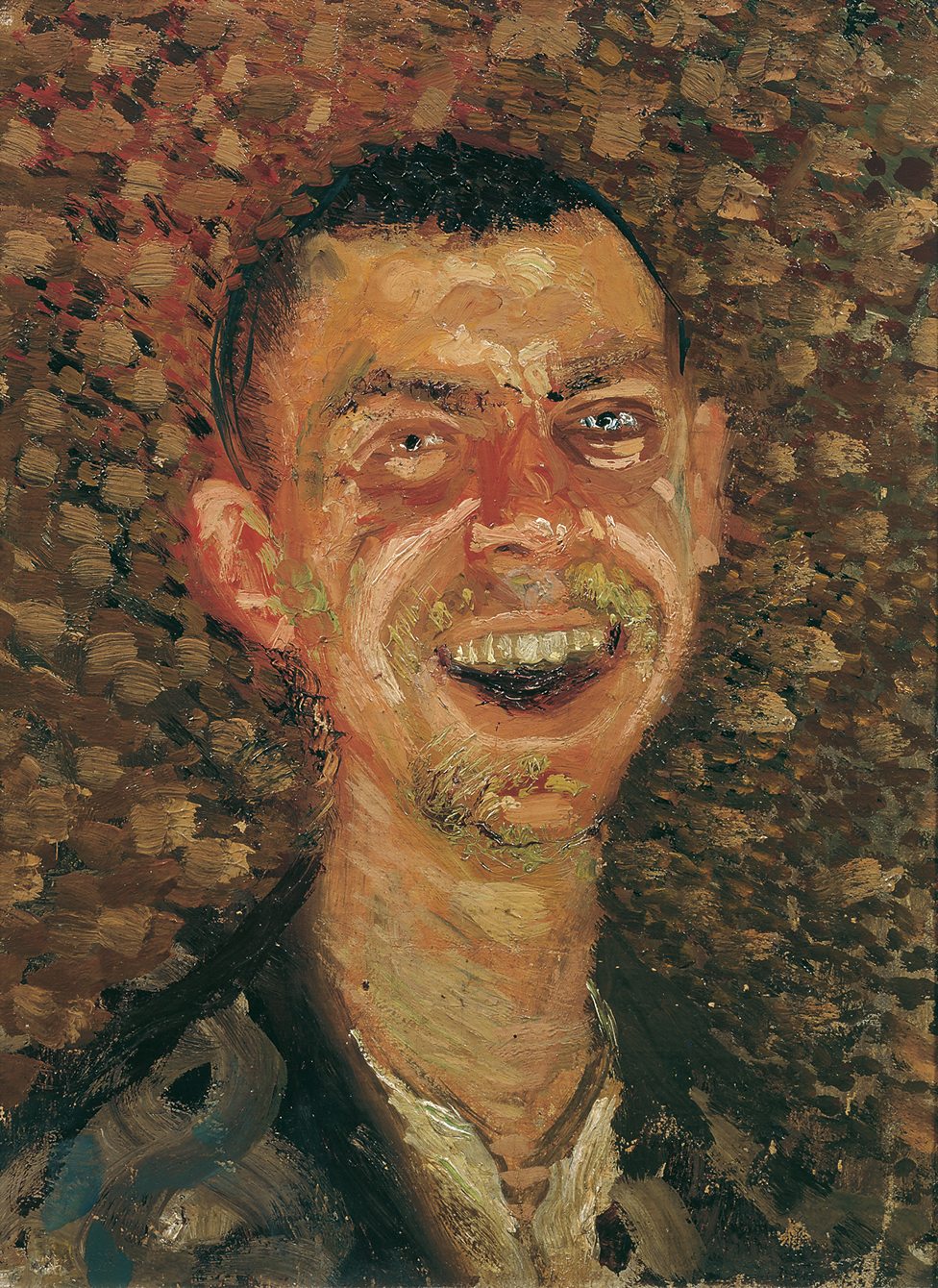

Gerstl’s final self-portraits in particular illustrate an expressionist immediacy of emotion: now aloof and dandyish, now buzz-cut and staring, now laughing maniacally, he presents image after image of himself as a parade of radically different people. The mutability of his style sees conventional figuration “buckle under the pressure of an all-out Expressionist technique” (Ross 2017), and these portraits are concretisations of bodily actions; expression itself, once wet, now dry. As Alex Ross writes,

Gobs of paint stream across the canvas, squeezed from the tube and spread with a fast brush, a palette knife, or the fingers. Faces melt into blurry masks, with splotches for eyes and mouths. Backgrounds are reduced to chaotic abstraction.

|

| Nude Self-portrait with Palatte, 1908. www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/asset/2QFAb3wfd-in0Q |

|

| Self-portrait in front of Blue Background, 1905. www.wikiart.org/en/richard-gerstl/self-portrait-in-front-of-blue-background-1905 |

To state the obvious, music is not painting. As Peter Franklin points out, “while Kandinsky could indeed stand, paint-pots to hand, and attack a canvas in a momentary outburst of expressionistic anguish, no such momentary spasm in the presence of manuscript paper could produce scores such as […] Erwartung” (Franklin 1985: 94). Erwartung is the object of my study here. A one-act monodrama written in 1909 over just a handful of days, it is pre-serial but certainly atonal. For Franklin, Schoenberg’s early expressionist works are necessarily structural; object, aesthetic lessons in Freudian dream interpretation, rather than dreams themselves. To Adorno, they are the "self-conscious model of a case study": art as psychoanalysis, made manifest through collaborative work.

Wishing to “portray how, in moments of fearful tension, the whole of one’s life seems to flash again before one’s eyes”, Schoenberg does nevertheless lean towards what John and Dorothy Crawford describe as the “expressionist urge towards simultaneity” (1993: 78). His contemporaries concurred: in 1912, Webern would write that “all traditional form is broken with; something new always follows according to the rapid change of expression”, and Adorno characterised Schoenberg's "actual revolutionary moment" (ie. more revolutionary than the emancipation of dissonance) as "the change in function of musical expressions", wherein "passions are no longer simulated, but rather genuine emotions of the unconscious--of shock, of trauma--are registered without disguise through the medium of music".

Wishing to “portray how, in moments of fearful tension, the whole of one’s life seems to flash again before one’s eyes”, Schoenberg does nevertheless lean towards what John and Dorothy Crawford describe as the “expressionist urge towards simultaneity” (1993: 78). His contemporaries concurred: in 1912, Webern would write that “all traditional form is broken with; something new always follows according to the rapid change of expression”, and Adorno characterised Schoenberg's "actual revolutionary moment" (ie. more revolutionary than the emancipation of dissonance) as "the change in function of musical expressions", wherein "passions are no longer simulated, but rather genuine emotions of the unconscious--of shock, of trauma--are registered without disguise through the medium of music".

Erwartung is rife with these aural "traumas". Violently sudden in its timbral and textural changes, the closest it comes to motivicism arises from some sparing ostinati (heard, for example, from the harp in bars 9-11 at 0:40 in the video below) and a few flashes of literalistic word-painting (the chirping of crickets on the celesta and tremolo strings in bars 17-19 at 1:20). Itself a psychoanalysis, Erwartung has been described as paradoxically "notoriously unanalysable" in its resistance of the Romantic musical structures of tension and release within forms of repetition (Franklin 1985: 95). Taking the gauntlet, commentators such as Crawford and Crawford have found characteristically Freudian "subconscious" structures such as three-note leitmotifs that relate to recurring symbols in the libretto: "night", "moon", and "blood". In a letter to Busoni, Schoenberg wrote,

I strive for complete liberation from all forms, from all symbols of cohesion and of logic […] no stylised and sterile protracted emotion. People are not like that. It is impossible for a person to have only one sensation at a time. One has thousandssimultaneously [….] And this variegation, this multifariousness, this illogicality which our senses demonstrate, the illogicality presented by their interactions, set forth by some rising rush of blood, by some reaction of the senses or the nerves, this I should like to have in my music (Crawford & Crawford 1993: 80).

The material spontaneity of an object such as a painting, or the lived spontaneity of a feeling in a moment itself, is paradoxically stretched across time. The aim, Schoenberg wrote in Style and Idea, was "to represent in slow motion everything that occurs during a single second of maximum spiritual excitement, stretching it out to half an hour" (1984: 105). This is, in many ways, the polar opposite of his approach to his 2011 Die glückliche Hand, in which "a major drama is compressed into about twenty minutes, as if photographed" (Schoenberg 1984: 105). In Erwartung, the blink of an eye is extended into something like a drama.

This drive not to communicate emotion but the embodied perception (in the “rush of blood”: think, again, of Kandinsky “attacking” a canvas) and, above all, experience is not—according to Crawford and Crawford—incidental to the “foreignness” of Mathilde’s psyche to Schoenberg. In a last will and testament that "may have been intended as a suicide note", Schoenberg wrote that he had "plunged from one madness into another," that he was “totally broken" (Ross 2017). In fact, Crawford and Crawford suggest that the Gerstl affair was what “aroused [Schoenberg’s] interest in feminine psychology”, and that the libretto to Erwartung directly relates to her (1993: 78).

Schoenberg commissioned the libretto from Marie Pappenheim, a recent medical graduate and poet, and part of an entire family of eminent Freudians. She would later go on to co-found the Socialist Society for Sexual Education and Research along with several counselling centres for sex workers--activity that, along with her and Annie Reich's feminist tract on the ethics of abortion, made her the target of police raids in the mounting conservatism of pre-war Vienna. Using stream-of-consciousness and free association techniques, Pappenheim's libretto consists of the shifting monologue of a lone, unnamed woman wandering a forest in search of her dead lover's body. The sexual politics are overt (to which the prominence of the feminine-coded "night", "moon", and "blood" attests); she kisses the corpse's lips in the same breath as implying that she killed him as revenge for infidelity.

Crawford & Crawford and Franklin all point out the parallels between Erwartung and Richard Strauss's Salome (1905) and Elektra (1909): the "demented shade" of both (or either) heroines "wanders off alone into the dark forest of the unconscious, 'searching'--perhaps for her Tristan, her John the Baptist, whose corpse she had stumbled upon but which she leaves behind at the last without remorse". In reality, though, Erwartung is far more ambiguous. In the dreamscape of the psyche, a body is never just a body, or even necessarily there at all. The corpse may or may not actually be there and the forest may or may not be literal: this music is the massive prolongation and unravelling of the "thousands" of simultaneous feelings, in all of their "multifarious [...] illogicality".

Crawford & Crawford and Franklin all point out the parallels between Erwartung and Richard Strauss's Salome (1905) and Elektra (1909): the "demented shade" of both (or either) heroines "wanders off alone into the dark forest of the unconscious, 'searching'--perhaps for her Tristan, her John the Baptist, whose corpse she had stumbled upon but which she leaves behind at the last without remorse". In reality, though, Erwartung is far more ambiguous. In the dreamscape of the psyche, a body is never just a body, or even necessarily there at all. The corpse may or may not actually be there and the forest may or may not be literal: this music is the massive prolongation and unravelling of the "thousands" of simultaneous feelings, in all of their "multifarious [...] illogicality".

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/A-1926734-1347797443-2924.jpeg.jpg) |

| Marie Pappenheim by Arnold Schoenberg, 1909. https://www.discogs.com/artist/1926734-Marie-Pappenheim#images/7514793 |

"Erwartung" translates as "expectation". If Schoenberg is attempting to unravel a multifarious moment of pure feeling for half an hour, presumably this the closest word we have to describing that feeling. What exactly are we supposed to be expecting? There is no revelation. A body is discovered, but we already knew it was there. From her first words, "hier, hinein?" ("shall I go this way?") to her last, "ich suchte..." ("I was searching..."), the Woman is utterly unmoored. As Franklin puts it, "what we searched for was never there at all. There were only the blind forces that prompted the search" (1985: 96). Salome knows what she wants ("bring me the head of John the Baptist!"), and gets it to the throbbing pound of orgasmic (and indeed tonal) release, but Erwartung has no such consummate climax. It "represents no spontaneous eruption from unconscious depths"; it can only be "the frozen illustration of a terrifying idea", and so the "registration of traumatic shock becomes the structural law" of a music "that has nothing to do with the illusory shapes of conflict and resolution, tension and climax" (Franklin 1985: 95; 66-67). The Woman never sings what precisely it is that she is searching for.

Unfulfilment is inherent to desire; one cannot exist without the other. To put it another way, you can't want what you already have. The crux of Freud's theory of dreams as the simultaneous revelation and cloaking of manifest and latent content relies on this structure. But fulfilment can only take place in time, in the teleology of climax. If Schoenberg and Pappenheim treat Erwartung as an analysis of a moment, then the condition of desire is suspended to the extent that its very object is totally unknown: "ich suchte..." trails off into ellipses, and the music evaporates into a contrary motion chromatic centrifuge. "The seismographic registration of traumatic shock becomes, at the same time", writes Adorno, "the technical structural law of music [....] Musical language is polarised according to its extremes: towards gestures of shock resembling bodily convulsions on the one hand, and on the other towards a crystalline standstill". The "bodily convulsions" of desire, and the absolute stasis of not knowing its object, generate the tension that structures Erwartung: not harmonic or dramatic suspension, but the at once vague and visceral condition of want itself.

Bibliography

Crawford, John C., and Crawford, Dorothy L. Expressionism in Twentieth-century Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Franklin, Peter. The Idea of Music : Schoenberg and Others. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1985.

McLary, Laura A. "The Dead Lover's Body and the Woman's Rage: Marie Pappenheim's Erwartung." Colloquia Germanica: Internationale Zeitschrift Für Germanistik 34, no. 3-4 (2001): 257-69.

Ross, Alex. 2017. "The Final, Shocking Self-Portrait Of Richard Gerstl". The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-final-shocking-self-portrait-of-richard-gerstl

Schoenberg, Arnold, Leonard Stein, Leo Black, and Joseph Auner. Style and Idea : Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg. 60th Anniversary ed. London: University of California Press, 2010.

Comments

Post a Comment