Patriarchy in the first movement of Hindemith’s Tuba Sonata

This was my first ever piece of musicological writing. I wrote it for my Oxford application while I was trying to escape the Royal Academy of Music. I was pre-transition in a male-dominated department, and almost as disenchanted with its lad culture as I was with the prospect of having nothing to do but tuba practice for the rest of my life. I really had no idea what musicology was until I was introduced to Feminine Endings, Queering the Pitch, and other such works of 'New Musicology'. While McClary and co. have their problems, I can never escape the fact that I probably never would've taken an interest in musicology without their work. Queer and feminist musicology made the study of music finally feel like it was For Me.

This essay is completely silly in all sorts of ways--clumsy, over-reliant on dichotomous thinking, weirdly revisiting the same musical material several times, wildly badly cited, and full of sweeping statements--but I still like it. Writing it cross-legged on my bed in my tiny, shared dormroom was probably the most fun I've ever had with my clothes on.

The later works of Paul Hindemith (from the 1920s onwards) are often categorised, albeit contentiously, as ‘neoclassical’, and the Tuba Sonata (written 1955) naturally falls into this generalisation. In 1920s Weimar, Hindemith subscribed to the ‘New Objectivity’ also seen in other art forms of the time, notably including Bauhaus architecture and some of Bertolt Brecht’s plays. This intellectual movement was reactionary against perceived the emotional excesses of the romantic period, and instead called for a leaner harmonic language, more restrained orchestral forces, ‘absolute’ music over programmatic, and a greater adherence to structure. In short, rational objectivity over romantic subjectivity. Igor Stravinsky justified this movement, saying:

The need for restriction, for deliberately submitting to a style, has its source on the very depths of our nature... Now all order demands restraint.1

The idea that rational ‘restraint’ is superior to romantic ‘excess’ is deeply rooted in the objectivity of renaissance humanist ideals, and runs in an obvious parallel with gender dichotomies.2 One of the most obvious manifestations of neoclassicism in this piece is its use of structure. Overall it takes the highly traditional three-movement form of Allegro, Scherzo, and Theme and Variations. This is used by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven alike, as is the equally as traditional sonata form which constitutes the first movement here. 3

Even in a post-war context, the sonata paradigm was an ideal formic practice for a neo-classicist due to its distinct clarity of structure, as well as its cerebral and intellectual processes of development. While the place of women in post-war society had undeniably transformed since the late renaissance, it is perhaps worthy of note that the 1950s saw something of a regression in women’s rights 4 , and it is essential to note that there was little or no academic discourse on the subject of gender politics in music until at least the 1980s.5 Therefore, the way in which gender clichés manifest themselves in his work is almost undoubtedly subconscious, and a product of the climate in which Hindemith lived.

Susan McClary depicts this manifestation as a ‘narrative paradigm’, ‘characterising’ sonata as a ‘polarised’ form:

The principal key/theme clearly occupies the narrative position of masculine protagonist; and while the less dynamic second key/theme is necessary to the sonata or tonal plot, it serves the narrative function of the feminine Other.6

While McClary acknowledges the feminine Other’s role as a necessary and defining antagonisation of the ‘masculine protagonist’, she still goes on to point out that ‘satisfactory resolution … demands the containment of whatever is semiotically or structurally marked as ‘feminine’’. In this way, she exposes the way in which the dichotomy between masculine oppression and mandatory feminine submission since the beginning of Western classical society is pertinently reflected and played out in musical form.

It could be argued that this rationale first manifested itself in music in a noticeably misogynistic way during the advent of Western classical music’s rigidly hierarchical diatonic system, which relies on the tension created by dissonances and the resolution of them ‘conforming’ back to their ‘superior’ consonances. Schoenberg retrospectively acknowledged the parallel between this strict hierarchy and the place of women in society, writing:

For our forbears the comedy concluded with marriage… the choice of scale brought the obligation to treat the first tone as the fundamental, and to present him as Alpha and Omega of all that took place in the work, as the patriarchal ruler over the domain defined by its might and will.7

Schoenberg here identifies the tonic as an allegorical ‘patriarch’, and suggests that in diatonic music, ‘feminine’ dissonances must not only eventually submit to and ‘marry’ the tonic, but that they themselves are ‘defined by its might and will’.8 This resonates noticeably with the tension between submissive and subjective romanticism and the ‘might and will’ of objective classicism, from which neoclassicism was conceived.9 In this way Schoenberg makes a very pertinent point about the subconscious politics of music which was not only composed almost exclusively by men, but by men who were part of a cultural movement which proclaimed ‘enlightened man’ to be the master of his own fate.

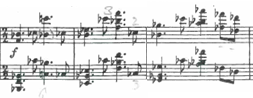

Hindemith’s use of sonata form here is in some ways traditionalistic, yet in others strikingly modern. For instance, the first movement can be divided into distinct sections which subscribe to traditional sonata form practices: an exposition of the main motivic material (starting in bar one), a fugato which constitutes the entire development section (starting at figure E in bar 49), and a recapitulation (starting at figure H). Its subject matter also conforms to convention insofar as the narrative roles of ‘masculine protagonist’ and ‘feminine Other’ can be observed explicitly in the movement’s ‘polarised’ principal themes. Indeed, the first subject is marked ‘forte’ and ‘allegro pesante’, and features an assertive and rhythmically simple strong-beat minim figure of rising ninths played by the tuba.

This figure embodies the archetypical masculine values of ‘might and will’ described by Schoenberg, and Hindemith’s use of the timbre of the tuba’s low tessitura here emphasises the more weighty and powerful capabilities of an instrument already generally perceived to be ‘masculine’, for now neglecting its lyrical capabilities and sweeter high register. This forms a very stark contrast indeed with the ‘piano’ second subject material which appears in the piano at figure A.

This gentle melodic material is far more conjunct and legato than its heavy counterpart, and bears a striking resemblance to nineteenth century music theorist A. B. Marx’s portrayal of a typical second subject theme as, 'a contrast to the first energetic statement… it is of a more tender nature, flexibly rather than emphatically constructed- in a way, feminine as opposed to the proceeding masculine'.10

Conversely to the emphatic tuba’s first subject, the second subject first appears for several bars in the piano alone, and in this way Hindemith could be seen not only to be polarising the melodic material, but also its instrumental treatment. However, he achieves this not by writing the tuba as an heroic and declamatory romantic soloist and the piano as a passive accompanist, but by stacking the two voices against each other in a sort of egalitarian intellectual discourse.11 The exposition section alone is rife with examples of this discursive strategy. For instance, while the tuba’s statement at the opening is upwardly emphatic with its wide, disjunct leaps, the piano does not passively accompany this proclamation, but instead challenges it with its own rising off-beat triplet figures.12 Moreover, Hindemith’s use of conflicting time signatures (6/4 and 2/2) and the wide void between the two instruments’ tessituras accentuates this rhetorical ‘dialogue’. Contrary motion in the left hand of the piano also serves to ground the counterpoint, keeping the rational and classical aesthetic of balance intact.

Nevertheless, the tuba does also answer to the piano in many instances. A good example of this is at figure D, where the piano plays the ‘grazioso’ codetta melody (first introduced at figure C), all the while underpinned by the tuba playing a version of the first subject. Still consisting of rising and relatively disjunct minims, its use of more dissonant pitches, a quieter dynamic, legato articulation, and more arch-shaped overall melodic line have rendered the once ‘mighty’ first subject almost unrecognisably ‘dolce’. This transformation of the ‘gendered characteristic’ of a musical idea purely through its melodic treatment is a crucial one in a feminist listening of this piece, in that its upheaval of fundamental clichés represents an intellectual dialectic between the two gender archetypes.

Another manifestation of such a transformation can be found directly after this, in bar 43, where the two voices, rather than rising competitively against one another, antiphonally exchange the same musical idea first heard in bars 30 and 31 of the codetta (the tuba’s version is now rhythmically augmented), rising in sympathy with one another. This creates rather an egalitarian discourse between the two, which is indicative of the intellectual developmental process intrinsic both to this piece and to the concept of sonata form itself. It is important to acknowledge that this level of motivic development has occurred before the development section proper has even begun. Perhaps then, despite having ‘submitted to a style’, Hindemith is already impressing his objective rationale upon the listener, and is already beginning to present his ideas not as superior and inferior, but as a conversation between equals.

A certain egalitarianism can not only be seen in Hindemith’s treatment of musical ideas, but also his entire approach to melody and tonality. By this stage in his career Hindemith had devised his own unique compositional system and outlined it in his book The Craft of Musical Composition (1937). Like his contemporary Schoenberg, he dispensed of classical diatonic harmony (a system which continued to be employed by many neo-classicists including Poulenc, Prokofiev, and Respighi), openly criticising its dictatorial nature in The Craft:

The diatonic scale with its limited possibilities determines the position and rank of the chords… the chord must blindly subordinate itself, and attention be paid to its individual character only as the key allows.

Determined to no longer be a ‘prisoner of the key’, as he put it, Hindemith used all twelve tones relatively freely. This seems to demonstrate a will to ‘empower’ the ‘individual characters’ of the tones forced into submission by the ‘patriarchal’ diatonic system. This is apparent right from the start of the Tuba Sonata, where the tuba’s opening melody falls just short of being a twelve-tone row, and is interrupted by a second B flat on beat 1 of bar 4 ( see figure 1).

In fact, in Program Notes for the Solo Tuba (1994) compiled by Gary Bird, Dorothy Payne describes this melodic statement as ‘startling’, calling it ‘a study in extreme chromaticism’. This implies a certain ‘freedom’ and lack of formal boundaries (she goes on to write that the piano part ‘moves with supreme disregard for even the fleeting tonal implications in the melody… the solo tuba may operate without fear of interference’). While this is an understandable reaction to such a stridently unfamiliar melodic line, Payne misses the point somewhat. The essence of this music’s radicalism really lies in the fact that the hierarchy of the diatonic scale is being subverted and replaced, not with what she perceives to be chromatic chaos, but with a new system altogether. Despite this music’s initial resemblance to serialism, rather than outwardly subscribing to Schoenberg’s system, Hindemith’s still makes use of an ‘Alpha Male’ tonal centre, and is therefore not freely atonal.

IHindemith establishes B flat as the tonal centre of this sonata by ranking each pitch in comparison with it, from the most consonant to the most dissonant.13 The following diagram appears in Volume II of ‘TCoMC’ to demonstrate the relationship of all twelve pitches to a tonal centre of C. Hindemith describes this as a ‘tonal planetary system’, and accordingly, all pitches are less ‘defined’ by the tonal centre to which they answer, but more ‘gravitated’ towards it.14 Perhaps it is no accident that Hindemith allegorically compares his tonal centre to ‘the sun’ (a fatherly, Apollonian figure in classical iconography) just as Schoenberg dubs the tonic in diatonic harmony ‘the patriarchal ruler over the domain defined by its might and will’. Hindemith maps out this ‘domain’ quite clearly here, usually by placing more consonant pitches on the downbeat of each bar, and more dissonant on the weaker beats.

The numbers below represent how far from the centre each pitch is:

Far from ‘moving with supreme disregard for even the fleeting tonal implications in the melody’, the piano’s accompanying triplets all move in fourths, and are more like broken chords than the ‘percussive’ and ‘random’ decoration which Payne perceives them to be. Hindemith also devised his own chord definition system to replace the ‘classical’, ‘feudal’ Roman numeral system, instead ranking chords from the most consonant to the most dissonant.15 This, too, is explained in Hindemith's Craft, along with examples of it applied in some analyses. Hindemith would analyse the opening bars of this piece accordingly, because the first four broken chords do not contain tritones, but exclusively fourths. This placing them in his ‘indeterminate’ category: very egalitarian in their equal distribution, and perhaps androgynous in their ‘indeterminacy’. Hindemith’s analytical system highlights the departure from the self-contained contrary motion fourths to the faster harmonic rhythm which starts in bar 3, complementing the tuba’s use of more dissonant pitches.

Evidently it is, as David Neumeyer writes, ‘a music which always has meaning, both intellectual and emotional, and brings that meaning forth clearly and cleanly’, and not the ‘extreme’ and irrational music of ‘disregard’ which Payne took it to be.16 Furthermore, this rather transparent, vociferous melodic writing is counterbalanced by a descending melodic figure in the tuba part with a tied minim-crotchet rhythm. This starts on bar 9 (I will label it theme 1b), and foreshadows the ‘less dynamic’ second subject (or McClary’s ‘feminine Other’).

The second subject begins at figure A in the piano part and is less tonally stable (perhaps reflecting the ‘insecurity’ of so many feminine archetypes). At first it places considerable significance on the pitch of B, which is repeated throughout and held as a kind of pedal. A semitone away from the original tonal centre, this B represents a significant harmonic shift (9 places from the centre of Hindemith’s 'solar system'. It also creates a kind of semitonal opposition with the B flat centre, which builds tension and is indicative of an agon between the two sonata themes, which is also outlined by A. B. Marx:

The second group in the exposition presents important material and closes with a sense of finality, but it is not in the tonic. This dichotomy creates a “large-scale dissonance” that must be resolved.

This is a largely Schenkerian perspective to take, and Schenker himself even described musical logic as ‘the product of procreative urges’.

Following the piano’s melody, the tuba enters with a ‘dolce’ falling figure obviously derived from and almost rhythmically identical to ‘1b’. It leads down to the piano playing the second subject again, a third lower. The fact that this ‘feminine Other’ forms such a stark contrast with the ‘patriarchal’ first subject in its direction, shape, dynamic, articulation, instrumentation, tonality and general character reinforces gender binaries and conforms to classically gendered ideals of dominance and submission, not to mention traditional sonata form practice. Indeed, the fact the second subject harmonically ‘recedes’ (or even ‘submits’) in each of its appearances is testament to this reading. Nevertheless, the falling ‘1b’ figure does serve as a kind of ‘middle-ground’ between the two opposing poles, and blurs the often rigorously drawn lines between music ‘gender’ clichés.

Despite his use of a binary exposition, an important convention to which Hindemith does not conform is diatonicism’s deeply-ingrained major/minor binary outlined by Schoenberg in his Theory of Harmony, who also compares it to gender binary:

The dualism presented by major and minor has the power of a symbol suggesting high forms of order: it reminds us of male and female and delimits the spheres of expression according to attraction and repulsion … this will of nature is supposedly fulfilled in them.

Schoenberg's comments on ‘attraction and repulsion’ are also reminiscent of Schenker’s ‘procreative’ analogy, and he goes on to express a longing for music which is ‘”asexual”… like the angels’. Indeed, Hindemith’s treatment of melody here could be described as “asexual”, with its indifference to diatonic drives of tension and release or the major-minor permutation. This is the inevitable product of his tonal ‘solar system’ which he professed to, 'free the composer from the tyranny of the major and minor’.

Nevertheless, arguably the most important aspect of Hindemith's system is the resolution of the dissonance which he sets up to a major triad. This is evident in the Tuba Sonata, especially in the final bars of the exposition section. Here, the tuba’s held F sharp is eventually complemented by an A sharp and C sharp in the piano. With both parts playing in the same sort of register and together creating a major triad, Hindemith indicates a sort of tranquillo ‘agreement’. However, the fact that this ‘agreed’ tonal centre is F sharp, a very distant tone from Bb according to the ‘solar system’ but the most consonant with B (the original ‘centre’ of the second subject), perhaps demonstrates that Hindemith is willing to ‘settle’ with the ‘dissonant Other’ second subject. And, more egalitarian still, the presence of an A-sharp enharmonic equivalent of B flat could even be seen as evidence of Hindemith reconciling the two seemingly irreconcilable tonal centres, however briefly.

Nevertheless, both this movement and the final movement end on a root-position B flat major triad. This is the resolution of the ‘large-scale dissonance’, and consequently the ‘patriarch’ has the final word, with every trace of the ‘dissonant Other’ vanquished. In chapter 4 of The Craft, Hindemith embraces this as an inevitability, writing that:

Music, as long as it exists, will always take its departure from the major triad and return to it. The musician cannot escape it any more than the painter his primary colours, or the architect his three dimensions.

He seems cheerfully resigned to the idea that his ‘sun’ is indeed the ultimate ‘patriarch’, and although he describes the desire to resolve towards it in less overtly sexual terms than Schenker’s ‘procreation’ or Schoenberg’s ‘attraction and repulsion’, he still deems this a ‘vital urge’ and part of the ‘natural order’. In short, Hindemith's neo-classical rationalism wins out, and the male-biased ‘balance’ of the gender hierarchy must be restored; the ‘dissonant Other’ quashed.

Therefore, to describe Hindemith’s use of tonality as ‘egalitarian’ is sometimes correct, but nevertheless a problematic over-simplification; his system still has a hierarchy, albeit an unconventional one. While he rejects the ‘tyranny’ of the major/minor binary, he embraces (however consciously) the dualism of sonata form. It would therefore be more accurate to describe his system as nonconformist, both in its rejection of received ideals of tonality and its rejection of absolute atonality. Hindemith's decision to make the opening statement of this piece fall tantalisingly short of being an actual serialist tone row only accentuates this reading; his could even be regarded as a ‘romantically’ individualistic dismissal of a system which was not only gathering a significant intellectual following, but also accused by critics of being excessively rationalistic. This exposes a fascinating contradiction between Hindemith’s intellectual ‘discourses’ and ‘submission’ to accepted traditionalist structures, and his radically individualistic refusal to ‘submit’ to the ‘patriarchal’ authority of pre-established harmonic disciplines. The rigorously structured nature of Hindemith's own system adds yet another dimension of irony to his already complex compositional identity.

Notes

1 ‘ An Autobiography’ Igor Stravinsky (1936)

2 Examples of the sibling dichotomies of romance vs. realism and femininity vs. masculinity are rife

throughout history, e.g. this quotation by James McGrigor Allen:

'To man belongs the kingdom of the head: to woman the empire of the heart’. Woman Suffrage Wrong in Principle, and Practice (1890)

3 Hindemith himself, however, would have disputed such an assertion. In a letter to Emmy Ronnefeldt he wrote:

‘I want to write music, not song and sonata forms!! Of course, if I write logically and my thoughts just happen to come out in an ‘old’ form, that’s all right. But in God’s name I’m not bound to keep on thinking in these old patterns!’ May 1917.

His assertion that something as rigid as sonata form ‘just happens to come out’ is highly demonstrative of the deep internalisation of Western classical values.

4 Broadly speaking, this was due to a myriad of cultural changes after the war, i.e. women no longer being required to work in factories, and the rise of mainstream media. The ideal of the ‘perfect housewife’ permeated popular American culture in particular, which was where Hindemith lived and worked in the early 1950s.

5 ‘When feminist criticism emerged in literary studies and art history in the early 1970, many women

musicologists such as myself looked on from the side-lines with interest and considerable envy… Yet

until very recently, there was virtually no public evidence of feminist music criticism.’ Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality Susan McClary (1991)

6 McClary 1991

7 Schoenberg 1911

8 A rhetorical parallel with this is the permeating Judeo-Christian conviction that ‘God made the woman from the rib he had taken out of man’. This is particularly relevant in light of eighteenth century music theorist Georg Andres Sorge’s depiction of the hierarchical relationship between the major and minor triads. He writes:

‘Just as in the universe there has always been created a creature more splendid and perfect that the others of God, we observe exactly this in musical harmony. Thus we find after the major triad another, the minor triad, which is indeed not as complete as the first… the first can be likened to the male, the second to the female sex. And just that it was not good that Adam was alone, thus it was not good that we had no other harmony than the major triad’. Vorgemach der musikalischen Composition (1745-47)

9 In light of this, it is perhaps ironic that Stravinsky called for neo-classicists to ‘submit to a style’.

10 ‚Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition’ (1845)

11 If the assignment of a gender or heroic status to a musical idea or instrumental voice appears flippant, Teresa de Lauretis offers the following view on traditional Western narrative:

‘The hero must be male, regardless of the gender of the text-image, because the obstacle, whatever its personification, is morphologically female… the hero is constructed as human and as male; he is the active principle of culture… she is a topos, a resistance, a matrix and matter.’ Desire in Narrative- Alice Doesn’t: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema (1984).

12 At figure B, the piano even plays a version of motif 1. Due to its duple meter and use of quavers, this has a rather more ‘angular’ feel to it than the tuba’s ‘swaggering’ triple meter rendition. In this way Hindemith sheds new light on ‘masculine’ material by retelling it with a different ‘voice’.

13 Hindemith’s choice of tonal centre is the fundamental of the German Baβtuba for which this was written. Whether or not this is significant is contentious, but it arguably affords the tuba part a greater sense of natural ‘assertiveness’ and ‘power’, as well as a more secure sense of ‘arrival’ when it resolves to B flat at the end of the movement (and the very end of the piece).

14 A parallel could be drawn here between the classical monarchical society of the 18th century and the hierarchy in diatonic harmony, as well as the somewhat different hierarchy of democracy and Hindemith’s tonal system.

15 This is Hindemith's chord table as shown in The Craft

Bibliography

‘An Autobiography’

Igor Stravinsky 1936

W. W. Norton & Company

ISBN-10: 0393318567

‘Woman Suffrage: Wrong in Principle, and Practice’

James McGrigor Allen

1890

London Remington

‘Selected Letters of Paul Hindemith’

Ed. Geoffrey Skelton

25th October 1995

Yale University Press

ISBN-10: 0300064519

‘Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality’

Susan McClary

24th July 2002

University of Minnesota Press

ISBN-10: 0816641897

‘Theory of Harmony’

Arnold Schoenberg

1911

University of California Press

ISBN-10: 0520266080

‚Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition’

A. B. Marx

1845

Breitkopf und Härtel

ISBN-10: 1176108476

|

‘Desire in Narrative- Alice Doesn’t

Teresa de Lauretis

1984

Indiana University Press

ISBN-10: 0253203163

‚Die Lehre Von Der Musikalischen Komposition‘

Paul Hindemith

1942

Schott

ISBN-10: 0901938300

‚Vorgemach der musikalischen Composition’

Georg Andreas Sorge

1747

Northwestern University

OCLC Number: 38716538

‘Program Notes for the Solo Tuba’

Ed. Gary Bird

1st August 1994

John Wiley & Sons

ISBN-10: 0253311896

‘Harmony’

Heinrich Schenker 1906

University of Chicago Press (1980)

ISBN-10: 0226737349

‘Paul Hindemith: The Man Behind the Music’

Geoffrey Skelton

1975

Victor Gollancz Ltd.

ISBN-10: 0575019883

|

Comments

Post a Comment