Intertextuality and Satire in the Roman de Fauvel's Motets

The Roman de

Fauvel (hereafter Fauvel) presents a single, allegorical narrative

attributed to Gervais du Bus. It tells the tale of a horse who “embod[ies] the

vices” in both deed and nomenclature, the name “F-A-V-V-E-L” being an acrostic

of flaterie (flattery), avarice (extreme greed), vilanie

(vileness), varieté (fickleness), envie (envy), and lacheté

(laxity). Fauvel also translates as “veil of falsity”.[1]

In Book I, the goddess Fortuna elevates Fauvel from his lowly stable to the

royal palace, where he has a custom-built manger and luxury hayrack installed.

Fawning churchmen make pilgrimages to see him, stroke his tonsured mane and

brush the dung from his tail. The France over which he presides is “bestorné”

(“inverted”): the moon rises above the sun, the king has authority over the

pope, and women have authority over their husbands. In Book II, Fauvel's ego is

inflated to the point at which he asks Fortuna for her hand in marriage.

Rejecting him, she instead offers the hand of Lady Vainglory.[2]

At their heavily allegorical wedding, there is a duel between the Virtues and

the Vices spectated by such guests as Flirtation, Adultury, and Carnal Lust,

all personified. Finally, Fortuna reveals that Fauvel's raison d'etre is

to reproduce more “Faveux” to corrupt the “fair garden of France”, and

to eventually become a harbringer of the Antichrist.[3]

There is a concluding but inconclusive prayer that the “lily of virginity”

might restore France to its former grace and piety.[4]

In its longest

extant interpolated manuscript form at the start of fonds français

146 (hereafter fr. 146), this “Beast Epic” is “grossly expanded” and “stretched

by the addition of a huge number of musical pieces”: the interpolations in

fr.146 comprise “169 musical items, 72 …

illustrations and 2877 lines of verse, the last almost doubling the length of

the poem”.[5]

In light of these numerous embellishments and the original narrative's

rhetorics of greed and luxury, it is unsurprising that Emma Dillon identifies

that “'excess' is a word often used to characterize fr. 146.”[6]

She describes its “complex confection of texts in a single manuscript; its

abundance of music …; the flamboyance of its illuminations”; reviewing Dillon's monograph, Sylvia Huot

reflects upon the “enormous scholarly attention” which Fauvel's demand

for interdisciplinary study has attracted, and the “ingenious readings” which

its intertextuality and satirical bent

has inspired.[7]

Fauvel's

satire is emphatically situated within the political climate of its time of

writing as “an ironical satire upon the deplorable state of the court of King

Philip IV and King Philip V, as well as that of the papal court at Avignon”.[8]

Textual clues situate fr. 146 at the beginning of the fourteenth century: for

instance, the arms borne by the Virtues in the tournament in book II have “the

date 1316 emblazoned on them”, confining the “fictive present” to the period

after Philip's accession.[9]

Fauvel's political commentary is particularly explicit at folia 10v-11r, where

the motets Se cuers ioans / Rex beatus / Ave and Servant regnum / O

Philippe / Rex regnum appear. Elizabeth Brown suggests that both were

pre-existing motets for Louis X, adapted for fr. 146 to refer to Philip V.[10]

Their presence here “at a particular concentration of royal interest” at the

junction of books I and II and directly before a miniature of Fauvel on the

throne (Fig. 1) bolster Elizabeth Brown's suggestion, supported by Emma Dillon,

that these are “didactic messages” for Philip

V to advise and teach him.[11]

Dillon takes this premiss further, suggesting that “this admonition also

embraces complaint aimed specifically at Philip, motivated by the changing

political scene at the time of the book's creation”.[12]

Servant regem's

texts' didacticism is explicit, with such statements as “mercy and truth and

also clemency save a king …. A wise king scatters the impious” in the triplum

and “O Philip …, use the counsel of upright men …, holding the rein of peace of

the church and judging the people in equity” and, inciting crusade, “attack the

race of pagans” in the motetus.[13]

Much like the Virtues/Vices tournament, this motet is a dialectic between the

things which a good king ought and those which he ought not to do, built upon

oppositions. This is further emphasised by the biblical allusions in the

triplum in contrast with the motetus' ceremonial, secular tone. Dillon further

notes how these texts are visually separated between fos. 10v and 11r (figs. 3

and 4), with the tenor (unusually for fr. 146) written out twice.[14]Servent

regem / O Phillipe is placed to the left of the image of Fauvel (fig. 4),

and Dillon relates this to a medieval trope of leftness being equated with

evil, referring to Fauvel and Lady Vainglory's left-handed marriage.[15]

Conceivably, this motet could actually be two-in-one, designed to be performed

first with the triplum and the tenor and then with the duplum and the tenor:

“each pair makes correct contrapuntal sense”, and these twofold advisory

complaints are thus each clearly articulated.[16]

The tenor's chant fragment is also sung twice, further binarily structuring the

motet. The dual oppositions of these texts are brought together as one, not

just within the motet's form, but by an unusual five-note rhythmic motif which

Dillon identifies at “moments of textual importance”.[17]

As the earliest surviving example of the kind of particular rhythm in Ars

nova notation—this is one of seventeen Ars nova notated motets in Fauvel,

only six of which are not found in other extant sources—“a consequence of

assuming that [a motet was] written for Fauvel is to place [it] at the

very centre of the early Ars nova and at the apex of the transmission of

this repertory.[18]

Dillon suggests that it would stand out to “informed eyes and ears”, appearing

three times in the motetus (bb. 1-22) and then again in retrograde (bb.22-8).[19]

Much like fr. 146, the motet brings these various texts together into a single,

emphatically and notationally new text with its own boundaries and performative

space, and uses the tensions between them discursively in order to make a

powerful, didactic impact.

Fig. 1: 11r, Fauvel on the throne, fr.146.

The motet Aman

novi / Heu Fortuna / Heu me on folio 30r also hangs upon

political subtext. The triplum alludes to Enguerran de Marigny, the disgraced

chamberlain of Philip IV who was hanged on the Eve of Ascension in 1315 and

left out, raindrenched, as an exemplar on the gallows of Montfaucon.[20]

Dillon writes that Marigny's “ascent to power was at least one of the models

for the Fauvel character”.[21]

This parallel of characterisation is also made explicit in the motetus, Heu

fortuna, which announces Fauvel's impending death. Indicated in the rubric

to be sung by Fauvel, Bent describes this as a “love-death song” to Fortuna.

Unusually, the tenor combines two chant fragments: beginning with the Office

for the Dead, it merges into Maundy Thursday.[22]

While this “appropriately morbid” dual liturgical association serves to “feed

into the pervading images of crucifixion and death in the upper voices”, the

Office for the Dead in particular encourages an audience “to read the liturgy

of the Dead as somehow belonging to the character of the horse”, cued by the

text “Heu me”.[23]

Juxtaposed with the “Heu Fortuna” love-death song, these multiple Fauvel

voices “cast [him] in the opening of the motet as participant in a deathly

liturgical chorus”: the motet's intertextuality becomes a platform from which

Fauvel can perform his own mortality.[24]

Envoking operatic dramaturgy, Bent describes Fauvel motets such as this

as “reflective 'arias' glossing the main text”, the motetus Heu Fortuna

being a “pivotal case” of “direct speech by Fauvel after Fortuna's rejection”.[25]

Dillon identifies this as an “ingenious new dramatic twist to the tale”: “in an

ironic reversal of its original intention, to woo Fortuna, we witness Fauvel’s

song succeed only in planting the idea for his own rejection and demise”, and

this irony is realised in the motet's performance, in which all of these morbid

texts at cross-purposes are sung and heard simultaneously.[26]

Fig.

2: 30v miniature, fr.146.

The intertextual

layers of the motet genre constitute meta-intertextuality within an already

heavily intertextual manuscript. Bent has written of a musicological tendency

to approach the motets in Fauvel “as if they were self-contained

compositions, treating fr. 146 as just one of several sources transmitting

them”.[27]

A close reading of fr. 146 defies such an approach. Andrew Wathey writes of

the extraordinary

richness, structure and depth of allusion here present …, tightly focussed and

integrated within the main theme of the literary work. The large body of

interpolated material, when not specifically composed for this version of

Fauvel, was brilliantly adapted, shaped and positioned—textually,

musically and pictorially—to amplify Gervès's work or to turn its messages to

the interpolators' new purposes. The musical compositions are emphatically

not marginal but vital to the interpolated Fauvel.[28]

With musical

interpolations covering the liturgical and devotional, sacred and profane,

monophonic and polyphonic, the motets in the Roman de Fauvel are a

select and scattered few facets of a complex bricolage of interacting

texts, brought teeming together in this single, object manuscript.

Butterfield's ekphrastic reading of fr. 146 is also one of materiality, telling

of how it “at once revels in and confounds such boundaries” as the margins at

the edge of each page.[29]

The mise-en-page of these already “excessive” texts; these

“line-drawings that stray over the boundaries of what can be seen, heard, and

grasped into performance”; this “succession of pages crowded with notation,

illustration, and text” culminates, she writes, in a “supreme visual shock”,

“powerful[ly]” borne of “a creative tension between the excesses of the

material and the finesse of the design.[30]

Viewed from this complex perspective, fr. 146 is a material critique of

materialism. In light of these interacting tensions mapped across a material,

pictorial object, Fortuna's parting words as Fauvel prepares to die and to

leave the material world impart, typically for the Roman de Fauvel, a

powerful ironic blow:

Pensee, Fauvel, maleüreux,

A la fin de cuer douleureux,

Et que du monde la figure

S’enfuit soudene en pourreture ….

Fauvel, cogita,

Quod preterit

Mundi figura.

Fugit subita;

Sic interit

Quasi

pictura.

“Think,

unfortunate Fauvel, what fate holds for faithless hearts and how swiftly the

flesh flees to dust …. Fauvel, reflect that the shape of the world is passing

away. It flees suddenly; it perishes like a picture.”

The motets of Fauvel,

fleeting musical interludes as they are, are only imperfectly congealed upon

fr. 146's pages, and Fortuna's poignant commentary on the transience of

material life heightens the lucidity of this already multifarious, viscerally

ironic text.

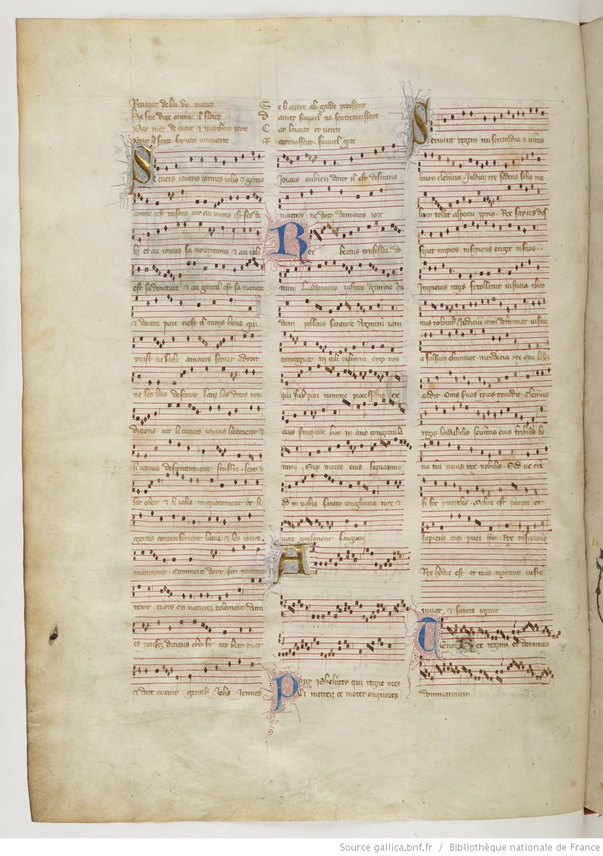

Fig. 3: 10v, fr.146

Fig. 4: 11r, fr.146

Bibliography

Avril,

François, Regalado, N., Roesner, E., Chaillou, & Gervais. (1990). Le roman de Fauvel in the edition of Mesire Chaillou de

Pesstain : A reproduction in facsimile of the complete manuscript, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, fonds français

146. New York: Broude Brothers.

Bent,

Margaret, & Wathey, Andrew, eds. (1998). Fauvel studies : Allegory, chronicle, music,

and image in Paris, Bibliothèque

nationale de France, MS français 146. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bent,

Margaret (1998). “Fauvel and Marigny” in ibid.

Butterfield,

Ardis (1998). “The Refrain and the Transformation of Genre in the Roman de Fauvel” in ibid.

Dillon,

Emma (1998). “The Profile of Philip V” in ibid.

Brown, Elizabeth (1980). “The

Ceremonial of Royal Succession in Capetian France: The Funeral of Philip V”. Speculum, 55(2), 266-293.

Clemencic,

René, Vitry, P., & Clemencic Consort. (1992). Le roman de Fauvel [sound recording]. (Musique d'abord). Arles, France: Harmonia Mundi France.

Dillon, Emma (2002). Medieval music-making and the Roman de

Fauvel (New perspectives in music

history and criticism). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dillon, Emma (2002a). “The Art of

Interpolation in the Roman de Fauvel”, The Journal of Musicology,

Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 223-263.

Huot, Sylvia. (2004). Review:

“Medieval Music-Making and the Roman de Fauvel”. French Studies,58(1),

79-80.

Sanders, Ernest. (1975). The Early

Motets of Philippe de Vitry. Journal

of the American Musicological Society, 28(1), 24-45.

Wathey,

Andrew. "Fauvel, Roman de." Grove Music Online. Oxford

Music Online. Oxford University

Press, accessed November 19, 2015. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/09372

[1]Bent and Wathey, 1; Långfors, A., & Le Petit, R.

(1914). L'histoire de Fauvain, réproduction

phototypique de 40 dessins du MS. français 571 de la Bibliothèque nationale,

précédee d'une intr. et du texte critique des Légendes de Raoul Le Petit, par

A. Långfors. Par. in ibid, 1.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Wathey

2015.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Ibid;

Butterfield 1998, 105; Wathey 2015.

[6]Dillon

2002, 7.

[7]Huot

2004, 79.

[8]Clemencic

1975, 3.

[9]Dillon

1998, 217.

[10]Brown,

235.

[11]Dillon

1998, 216.

[12]Ibid,

217.

[13]Dillon

1998, 221.

[14]Ibid,

220.

[15]Ibid.

224.

[16]Ibid,

220.

[17]Ibid,

221.

[18]Avril

1990, 25; Bent 1998, 40.

[19]Ibid,

221.

[20]Bent

1998, 36.

[21]Dillon

2002a, 256.

[22]Bent

1998, 37.

[23]Dillon

2002a, 152.

[24]Ibid,

153.

[25]Bent

1998, 40.

[26]Ibid,

258.

[27]Bent

1998, 35.

[28]Wathey

2015, emphasis my own.

[29]Butterfield

1998, 105.

[30]Ibid,

105.

sakarya

ReplyDeleteyalova

elazığ

van

kilis

K5KV0

görüntülü show

ReplyDeleteücretlishow

CHQ77

ankara parça eşya taşıma

ReplyDeletetakipçi satın al

antalya rent a car

antalya rent a car

ankara parça eşya taşıma

JİMG8

62C57

ReplyDeleteVan Evden Eve Nakliyat

Adana Evden Eve Nakliyat

Ünye Evden Eve Nakliyat

Afyon Evden Eve Nakliyat

Silivri Çatı Ustası

72C57

ReplyDeleteBursa Lojistik

Tokat Parça Eşya Taşıma

Gümüşhane Lojistik

Çerkezköy Cam Balkon

Sinop Evden Eve Nakliyat

Bolu Parça Eşya Taşıma

Çanakkale Şehirler Arası Nakliyat

Ort Coin Hangi Borsada

Xcn Coin Hangi Borsada

11F58

ReplyDeletebedava sohbet odaları

kütahya goruntulu sohbet

sesli sohbet siteleri

Antalya Mobil Sesli Sohbet

sohbet muhabbet

kastamonu rastgele sohbet

malatya yabancı görüntülü sohbet siteleri

trabzon sohbet odaları

eskişehir canlı ücretsiz sohbet

7FB86

ReplyDeleteÇorum Sesli Görüntülü Sohbet

bedava sohbet

Mardin Sohbet Chat

Giresun Sohbet Chat

malatya görüntülü sohbet siteleri

karaman en iyi görüntülü sohbet uygulamaları

eskişehir görüntülü sohbet sitesi

Siirt Sohbet Muhabbet

antep bedava sohbet chat odaları

32138

ReplyDeletekızlarla canlı sohbet

ankara görüntülü sohbet odaları

rastgele canlı sohbet

tekirdağ kadınlarla rastgele sohbet

Antep Mobil Sohbet Siteleri

konya kadınlarla sohbet et

ısparta Rastgele Görüntülü Sohbet Uygulaması

hatay random görüntülü sohbet

Bedava Sohbet

YJUYKIUYKJK

ReplyDeleteشركة تسليك مجاري بالاحساء

شركة عزل اسطح بالقطيف UvA7uGW6QS

ReplyDeleteشركة مكافحة حشرات ygL9sHid7C

ReplyDeleteشركة مكافحة حشرات بالجبيل sVQUGFSn9k

ReplyDeleteشركة تنظيف بالاحساء d0isHugwur

ReplyDeleteB375305F91

ReplyDeletetiktok takipçi arttırma